Призма инклюзивности. “Draw a Teapot”: How a simple exercise gave me new insights on human biases (2018)

As part of the preparation for my Inclusive Design workshops, I’m usually looking for new exercises or try to reevaluate the existing ones. And some activities emerge from the situation in the room when I’m about to illustrate some concept.

This story is about how the “Draw a Teapot” exercise was born, its evolution and my reflections on it.

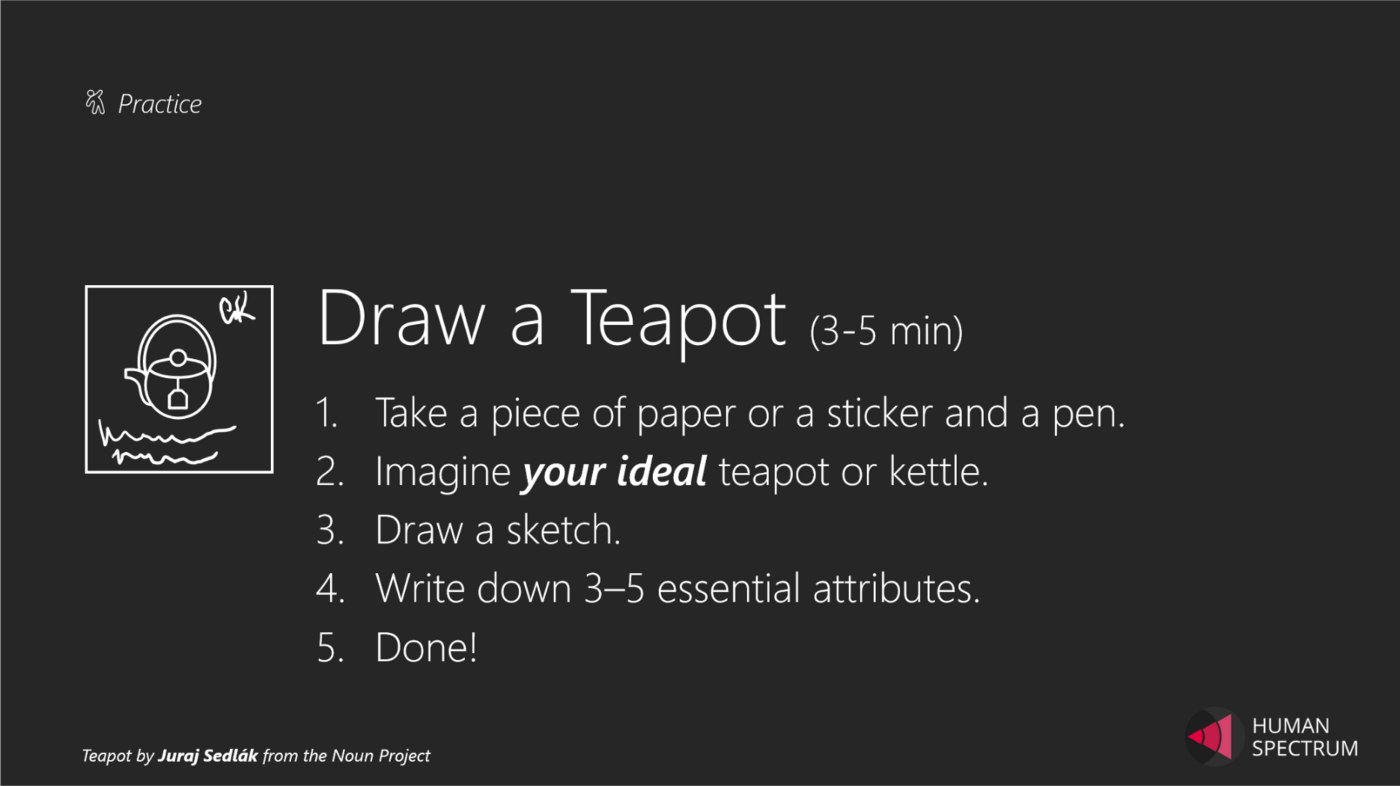

But before we move forward, let’s begin with the exercise itself. It’s small and straightforward, and usually takes no more than 2–3 minutes.

- Take a piece of paper or a sticker and a pen. You can use a drawing app on your device as well.

- Imagine you ideal teapot or kettle. Something that makes sense personally to you, but also a realistic one (e.g.,

without quantum effects). - Draw a sketch. Don’t pretend to make a piece of art; it is not a drawing skills challenge.

- Write down 3–5 essential attributes. Again, something that touches you: e.g., weight, color, material or unique features.

- Done!

We will return in a few minutes back to your drawing with a second part of the exercise.

Origins

Why would anyone draw a teapot (unless you are taking an art class)? Is there anything special in this device? If you are a collector or a manufacturer, you might say “Yes!” But for me it is just a commodity, there is nothing special,.. except that most of the people are familiar with it. It is one of the

things we use every day: in the majority of nations and cultures.

We all know that there are many kinds of teapots or kettles or water boiling devices. Is it possible that our perception of such a casual thing could be affected by our biases, cultural and personal stereotypes?

That was the initial question I asked myself while trying to find an illustration of gender stereotypes in front of fifteen or so designers — something that would touch every one of them and also would be practical. Practice is good because it makes you remember things for a much-much longer timeframe. And it should be funny as well.

I quickly gave every person a sticker and asked to draw a teapot, write down some attributes and put a name on it as well. I was curious whether there will be any significant difference among these smart people (both male and female)? And there was!

Usually, you should expect that there are various points of view and every teapot is individual. You might also assume that there could be some man or woman related patterns. But the possible diversity among the “male teapots” and the “female teapots” was not the picture to be illustrated or discussed in the first place.

My next question was: how do attendees of the workshop perceive another gender? Biases were the target to be exposed. So, a gave them a second part of the exercise:

Do the same, but now imagine and draw a teapot for another gender, write down attributes for another gender. If it is difficult, look at a person of another gender in the room and draw a teapot for that particular person.

Great! Now we have a new set of opinions in the room.

To make it easier for you to follow all the rest, I would ask you to repeat that exercise one more time but with a small change:

- Find a person of another gender/age/etc. (anything that you could refer as diverse from you). And ask that person to:

- Take a piece of paper or a sticker and a pen (or use an app).

- Imagine an ideal teapot or kettle for you (yes, you!).

- Draw a sketch.

- Write down 3–5 essential attributes.

- Give it back to you. Done!

So, you also have two teapots to compare: one drawn by yourself and another drawn by somebody else for you. Pay attention to one simple fact: both are targeting the same person — you. Is there any difference?

Back to my room. I just doubled the number of opinions in the class, and in a particular way. I knew:

- What teapots men would design for themselves (men).

- What teapots women would design for themselves (women).

- What teapots men would design for women.

- What teapots women would design for men.

And guess what? These were four different opinions!

The actual list of features depends on the group, but what I found interesting as a repeating pattern is the following (just in case, it was not quantitative

scientific research, just some subjective observations of six different groups of people related to IT in Russia):

- Men tend to mention for some technical features like a remote control; women focus on practical aspects like usability or auto-scaling.

- Women language even on a small sticker is more detailed and diverse; men are trying to be specific and short.

- From a male perspective (like my own biased) it was surprising to see women requesting features like “a teapot made of surgical steel” or “with tracking usage patterns.” But women usually were not surprised by any men requests.

- In practice in many core aspects (e.g., volume, material) the ideal “men-men teapot” is closer to the “women-women teapot” than to the “men-women” or “women-men” ones.

- And yes, there were some cultural stereotypes expressed — like “women are more focused on beauty” and “for men it should be a minimal working simplest man-thing.”

I will discuss some other nuances below, but the main point here was that people saw not just that there is an alternative point of view (like man vs. woman), but also that they all have biases that don’t match the reality.

In other words, we all have biases. And now we know that even our perception of teapots could be biased as well. :)

Evolution & Insights

Over time I noted that I always had at least one person in the group who would ask like “why should I draw a different teapot for another person or another gender?”

But I never asked them to do that. “I didn’t ask for a different teapot; I asked to design for a different person.” And that challenging me person usually drew the same picture twice.

It was ok, but I quickly realized through a little bit of experimentation with the exercise setup, that I was dealing with something different than just one aside question:

First of all, if I didn’t put enough time between these two steps (draw for yourself and draw for another person), too many people realized that I was tricking their minds to expose their bias. So they switched on intellectual mode and drew more or less the same. Good catch for them, but a good one for me as well. Next time I ensured we changed the context and we had one hour plus between the steps. Now workshop attendees drew more like what they thought, not what they wanted to look like.

Second, it turned out that for some people my request itself — to draw something targeting another gender — looked like a sexist request, because they realized that I was about to provoke a gender bias.

Think about it: Meanwhile, I didn’t ask to draw any specific male or female teapot, my specific request to draw it for another gender supposed like there should be a male or female teapot. And that kind of requests not just provokes to express existing bias, but also provokes extra imagination based on that bias. And in some cases a fair push back.

The point here is that the question itself might provoke a biased way of thinking. Imagine if I’m asking you: “I’m looking for a gift for my niece, could you help me to choose something nice?” Then you start thinking: “Ok, you are looking for something for a young girl…” Alternatively, I could not specify the gender, and maybe you will ask instead: “What is she or he interested in?”

And for a group studying Inclusive Design, it seems to be critical to highlight not just their bias, but also that this bias could be manipulated or provoked. Each time you design something that could be biased (e.g., based on gender, age, race, culture, education, profession, etc.) you should double check: “Do I provoke a biased behavior with my design or I do not?”

I also started to practice a light version of bias exploration: instead of asking to draw an “another gender teapot” I proposed to draw a “teapot for a neighbor.” Mostly that form of exercise didn’t highlight any specific bias, but it still showed that there are different points of view.

At the end of the day (or workshop) we all agree that there is no reason why there should be any specific male or female teapot. Meanwhile, it does not exclude that there are teapots for various scenarios and contexts. We know it logically, but we still have biases. And unless we begin training ourselves to recognize such behavior, it will be exposed or realized without us even noting it.

4 Points of View

In one of the groups I was asked, “Ok, we got this diversity and bias theme. How should we use this teapot example in our design process?” A hard question. Is this example scalable to other situations?

After a short discussion, we figured out, that yes. Absolutely!

Imagine that we are designing interaction between two people (or groups of people). A direct one like “a manager meets with a client in the bank office”, or an indirect one like “an e-commerce website proxying end-customers and merchants”.

Usually, we try to identify the goals of each party (“self-reflection”) in that interaction. And then we use our designer experience and tricks, and magic to align these two points of view into one communication. I mean, we behave like we are the smartest persons and are capable of connecting these two people and their goals in a right way. I guess, sometimes we fail. :)

It turns out that in addition to these two points of view, which we are trying to align, there are at least two more — the “feelings of others” for each participating actor:

It is a mental model of the partner in a dialog or a play, which by the way could be biased. That is why we are trying to expose and understand it. Moreover, that “feeling” is usually not declared or shared with you, but it still might be an active player, sometimes intentionally hidden from you.

In one group participants shared with me the following story: they are building a website connecting private investors and small and medium businesses looking for money to participate in various tenders. Occasionally they found that a group of investors created outside of the system a blacklist of borrowers. It was a strong manifestation that on top of their personal goals they also had an opinion on the other side.

The problem here is that if you directly ask somebody on his or her biases, it would be a rare case when they share real feelings. Why? Because… it requires a high level of self-awareness and trust.

Sometimes in design, we refer that ability to read and understand the “feeling of others” as empathy. For example, if you design communication between a manager of private banking service and a customer, it is essential to track their personal goals, but also you should understand their perspective on the other party of communication.

The next level of empathy is when you begin reading other’s empathy on somebody else.

For customer: “What do you think is the goal of your manager? How is this communication between two of you designed from his side? If you were on his place, what would you ask somebody like you about? How do you think this interaction impacts his bonus? What information would you try to extract from the customer if you were him?”

For manager: “What are the goals of your customer? If it were you on the other side of the table what would you tell, share, or avoid sharing? What would you do in her case?”

And reflecting back on the teapot-exercise, you might ask both parties to describe how they would design this interaction for themselves, and for the other side:

Also, pay attention to how we are trying to trick a person’s mind by putting them into target shoes and idealizing the situation.

For sure, you might also develop your own exercises and tricks to uncover differences in points of view and to highlight hidden biases.

So as these perceptions of other parties of interaction are active actors, they should be discussed and examined during the design process. In other words, when we create an interaction between two parties, it is our job to design or influence the perceptions forming around that interaction.

Sometimes it means that we should educate our users. For example, if you are building a store of apps (like Microsoft Store or Google Play), maybe you should consider providing extra-insights on customer feelings to developers and ask yourselves: “How might we create more empathy towards developers among end users?”

Sometimes it means that these feelings should be captured and exposed in the experience itself: like we already do with ratings of riders and drivers in taxi apps.

And sometimes we should take it into account and use that knowledge to set up right expectations.

For example, if you are launching a global product from a country X, you should be aware of the perceptions of the product itself, of the niche of the product or industry, of you as a company or indie developer, and of your origin country in other parts of the world. And what I see globally (for example across Kickstarter, startups and various ICO projects) is that sometimes founders are mimicking or intentionally diversifying their origin countries depending on where their audience is.

Summary

- Draw teapots. Ask others to draw teapots. Teapots are good. Sketching is good.

- It is crucial for designers, product creators, developers and everyone to understand that we all have biases. There is no ideal person. It is not like “I’m smart, and others are biased.” The question is always on the bias-surface, and whether we can overcome it with our intelligence, experience, data and so on. We can’t do it unless biases are named.

- Bias could be manipulated. It can be provoked, intentionally or unintentionally. If you create a product, if you design a questionnaire, if you organize an event and so on — you are responsible for ensuring not adding more bias and reducing already existing bias surface.

- When you design a communication, you should take into account not just goals of participating parties, but also what perception each of them has on others. These perceptions are also the subject of design. Even the perception of you as designer or mediator might be the subject of design.

- Usually, the bias is not something people are ready to share; sometimes they are just not aware they have some. That is why we use various tricks to identify or highlight them. But when you reflect on biases you should also understand: it’s not like “bias is some evil,” from mind perspective it is a shortcut in decision making. So it’s also designer’s job to propose an alternative shortcut, which should be better, but also might be biased. Making the world better is a journey.